As Photos, mostly moves into 2024, the free monthly issue, and the mid-month Dispatches, will continue and there will be new, additional content each month for paid subscribers. As next year transpires, I will bring criticism, interviews, discussions, guest posts, collaborations, and more street photography to paid readers. This winter, however, I begin my paid content with my inaugural, annual State of Street Photography essay.

As I come to the end of my savings that have kept me since I left corporate life in April of this year, contributions and paid subscriptions from the readers of Photos, mostly will be invaluable in helping me turn my photography and writing into a viable way to pay my rent, so to speak. Thank you to all readers for your support and our conversations through 2023, and thank you to the handful of paid subscribers who upgraded in anticipation of this essay.

If you aren't yet a paid subscriber and would like to read the next 7,000 words, or listen to me stumble through them in just under an hour, then please consider upgrading - it’s cheap as chips. Literally.

**Note: this is a long one, around 7,000 words, so if you are reading it via email, it may come to an abrupt end, click here to read the whole essay on Substack.**

Have a great holiday season, and let's get started…

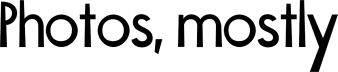

Street photography, with its many philosophies and practices, and its long and eventful history, has been a cornerstone of the art of photography since its very beginning. One could make a convincing argument that the first photograph to contain people, Daguerre's The Boulevard du Temple (1838), was a street photograph - a shoeblack and his customer stopped long enough to be caught on film through the French photographer's long exposure. Before it was even known as such, street photography, from that of Atget to Webb, has recorded the modernisation of our world, and the vast assemblage of people that have inhabited it.

Several recent articles on Substack have been critical of the current state of street photography. From writers who argue it is dead, through others who worry it may have lost its soul, to those who posit it has no place in our privacy-conscious world. My own view on the state of street photography is somewhat more positive and while we must reflect on ethical, educational, technological, and artistic considerations and accept some change may be necessary, in this, my inaugural annual analysis of the state of street photography, I believe its present and future are bright.

Online Spaces

Photos, mostly was born of my frustration at the mediocre, insipid street photography found across social media on hashtag-streetphotography. Hasty snapshots of the backs of heads, distant photos of people on their phones, backgrounds photographed with passers-by where the ill-considered juxtaposition says nothing to the viewer, and vapid, reaching captions were all on display. Like many creative communities I experienced in my time in music, toxic gatekeeping was a problem in these online photography spaces, and as always those with the loudest voices had the least to say while simultaneously masking a distinct lack of ability. Instagram, Reddit, and at the time, a pre-Musk Twitter, among others were becoming poor choices to find community.

Much has been written of Meta's endless attempts to compete with other platforms through Instagram's pivot to short-form video rather than serving its legacy of photography. With Stories, Reels, and interminable ads, sharing photography on Instagram has become intolerable. It is a daily slalom, manoeuvring between this hashtag and that, avoiding the algorithmic pitfalls in the hope that a photograph may be seen by even the smallest percentage of those that follow, and more often than not finding oneself bitterly disappointed at the lack of reach. Beware, of course, the curated accounts, especially those that offer to feature your photography for a fee. If it looks too good to be true, it often is. On Instagram's street photography-focused hashtags there is some excellent work to be found, however, much truffling has to be done to discover it.

After leaving Instagram behind, I turned briefly to TikTok, however, the interminable grind required to cement a presence there was an immediate deterrent. The analogue community on TikTok is vibrant, however, with exceptions, the street photography community that was served to me seemed light on substance. So many so-called street photographers lumped in with those what do you do for a living? irritants. In a TikTok skit, Friends actor Courtney Cox highlighted the obstacle course of influencers to be conquered by only walking down a New York street. TikTok may be a path for younger street photographers, but there is too little actual photography for me.

Reddit, not an online space famous for its harmony, is rife with the worst type of gatekeeping. On the platform's most popular street photography Subreddit there was a fundamental debate about the very nature of street photography. Many users went so far as to characterise candid photography as abuse. The gatekeeping Subreddit owners and entitled moderators made the experience of even only lurking on these communities an unpleasant one, and not one that can be recommended.

So far, so bleak. Elsewhere, however, online street photography communities are welcoming and thriving. Many users are eschewing larger platforms for a more niche experience. Smaller social media apps are often spoken of with fondness. Vero launched with some intention of eschewing algorithms and filling the space Instagram was leaving behind. Foto, A new platform, launched a private beta and there have been positive signs emerging from behind the paywalled doors. As Twitter fell apart and many users decamped to federated spaces such as Mastodon, it opened the door for photographers to try a federated platform and many took to Pixelfed. For film photographers, several niche platforms appeared and disappeared just as quickly, however, Grainery, while small, is an interesting place to find film photography, some of it from the street.

Longer-form video content is a popular way to share street photography and discussions around the practice and philosophies of the art. YouTube remains the hub for all such creators. Street photography on YouTube, however, does seem to provoke strong feelings from the wider community and many of these Marmite creators are loved or hated with some intensity. Of the throng, Sean Tucker and Paulie B are 2 prolific creators who stand out.

Do It Yourself

Choosing to step back from social media, most of my work is now found on my website, and street photographers would be wise to set out their own stalls. What use is a website, however, if no one visits? Medium was recommended, and while there is limited street photography content found there, I opted to try something new. To complement my website, and tempt readers towards it, Photos, mostly was born: A Substack newsletter combining platform-exclusive essays and recommendations with a digest of my other writing and photography from across the month. Growth was slow, and it was after some perseverance that I began to both find my audience and discover other photography Substacks out there. Wesley Verhoeve, Andy Adams, Andrew Eberlin, Patrick Witty, and Alice Zoo are writers of just a handful of excellent, recommended photography newsletters. Street photography is still a niche on the platform, though it is growing and there are excellent street photographers to be found there. Other than , two notable and recommended accounts are Storydrops, and the African-focused Tender Photo.

Across the internet, street photographers who have developed their own websites offer a wide gamut of work, though it can be difficult to focus in on those worthy of attention. Many magazines and blogs collect some of the best street photography out there. Street Photography Magazine and Streetphotography.com offer both excellent photography and essays on the topic. Lensculture has a wider remit but offers a great deal of street photography. Websites of collectives and groups are also fecund spaces to find work from the top drawer. Up Photographers, in-public, the Archive of Public Protests, and Un-Posed are a few that I return to regularly, however, there are many more to be found and forming a collective is a common, recent way for street photographers to organise themselves.

As 2023 comes to an end, it is clear that the spaces in which street photography exists online are in the process of material change. In their attempt to remain relevant, Web 2.0 platforms are forfeiting many longtime users. New platforms are emerging, however, it will take time to discover whether they have staying power. Many former Twitter users feel burned after losing vast numbers of followers when leaving the platform. Advice from all quarters this year is to control one's own following. Build a website, maintain a mailing list, and work directly with readers and viewers. Growth may be slower, but one's audience is not at the whim of a tech billionaire.

Education

Education in Street photography is a cottage industry in and of itself. From Substacks such as Photos, mostly through films, books, online courses, and workshops, to mentorships and masterclasses. Learning to be a better street photographer has never been quite so easy, though with such choice comes a difficult decision on what option is best.

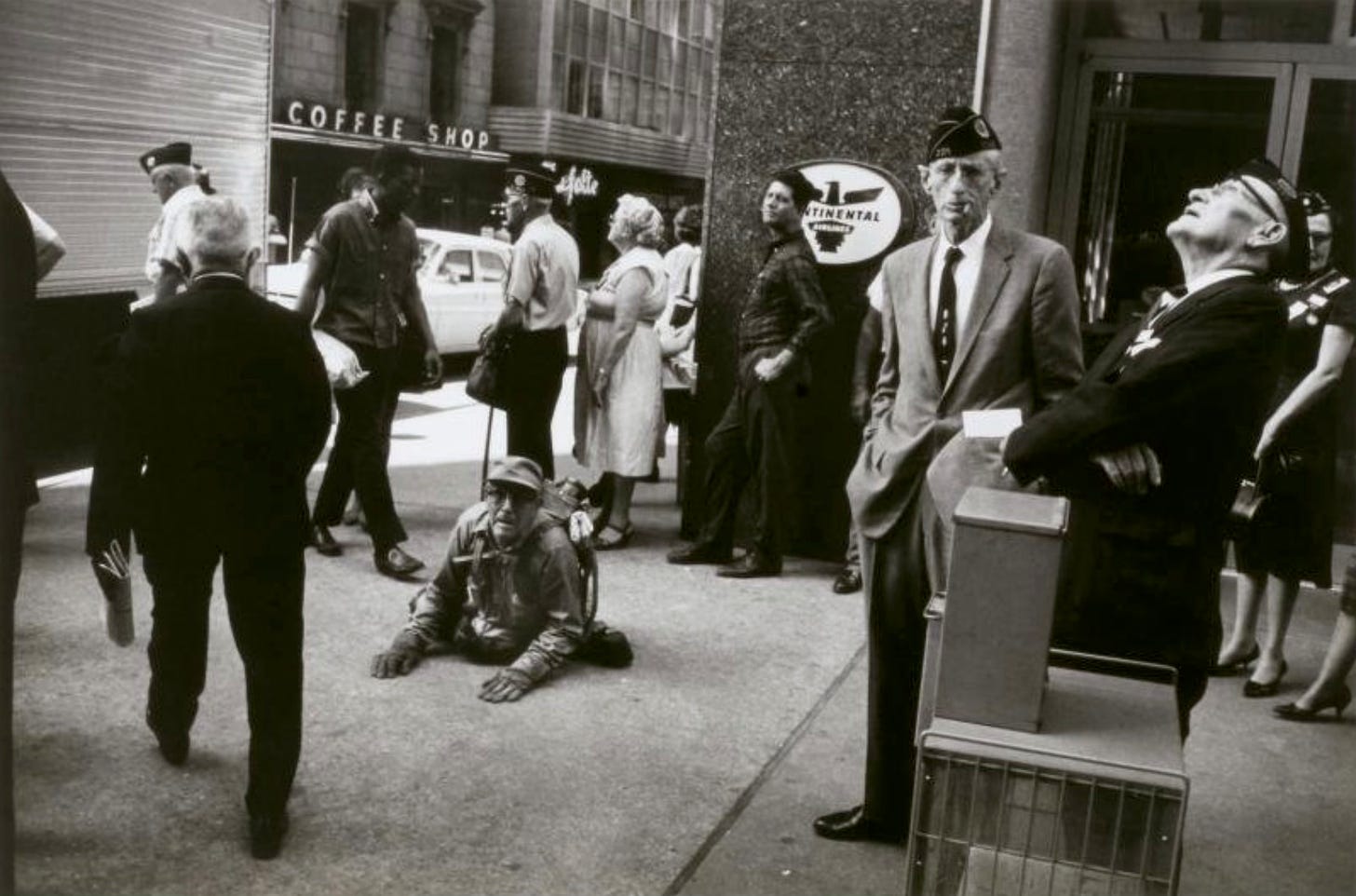

Street photography instruction and coaching come from a variety of sources, both active and passive. The passive, ingesting education from zines, books and films, is most often the starting point. Whether from classic, acclaimed photo books, expansive compilations, self-printed zines, or documentary films, much inspiration and learning can come from reviewing the stories and street photography of others.

There is no one-stop shop for street photography zines and short-run or self-published books, however, across the world, you will find them stocked and displayed in galleries and photo book boutiques. As with any creative art in the amateur or semi-pro sphere, the spectrum from mediocre to spectacular is wide, so have a flick through a zine before buying, or if online, review an artist's work to make sure it's for you.

Books

Many online bookstores allow one to avoid turning to Amazon, though in the case of the smaller stores waiting times can be long. My friend Dan, of the Desire Paths newsletter suggested Setanta as a great place to find new street photography books without having to spend hours trawling the internet. The website has a comprehensive street section and also boasts a collection of rare books and its own recommended list.

Same as it ever was, many useful and exciting photo books fall out of print and can only be found on the second-hand market. This year, for instance, I've found affordable copies of Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb's Aperture publication On Street Photography and the Poetic Image, and Geoff Dyer's The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand, on eBay.

In 2023, the compendium that has made the biggest splash has been Stephen McLaren's collaboration with Matt Stuart. Their book, Reclaim the Street is a showcase of work by over 100 street photographers from around the world, both those well-known and others emerging. A major retrospective of Saul Leiter published this year was also anticipated and has not disappointed. There have been new books by Alex Webb, Richard Kalvar, Daidō Moriyama, and Phil Penman among others, and the Cafe Royal Books series has published several small collections of street photography from the 70s and 80s. Books that I consider required reading for street photographers, such as Robert Frank's The Americans, and Magnum's Contact Sheets, also remain in print. More traditional educational fare such as Matt Stuart's Think Like a Street Photographer, Moriyama's How I Take Photographs, and Colin Westerbeck's history of street photography, Bystander, also remain enduringly popular.

Film

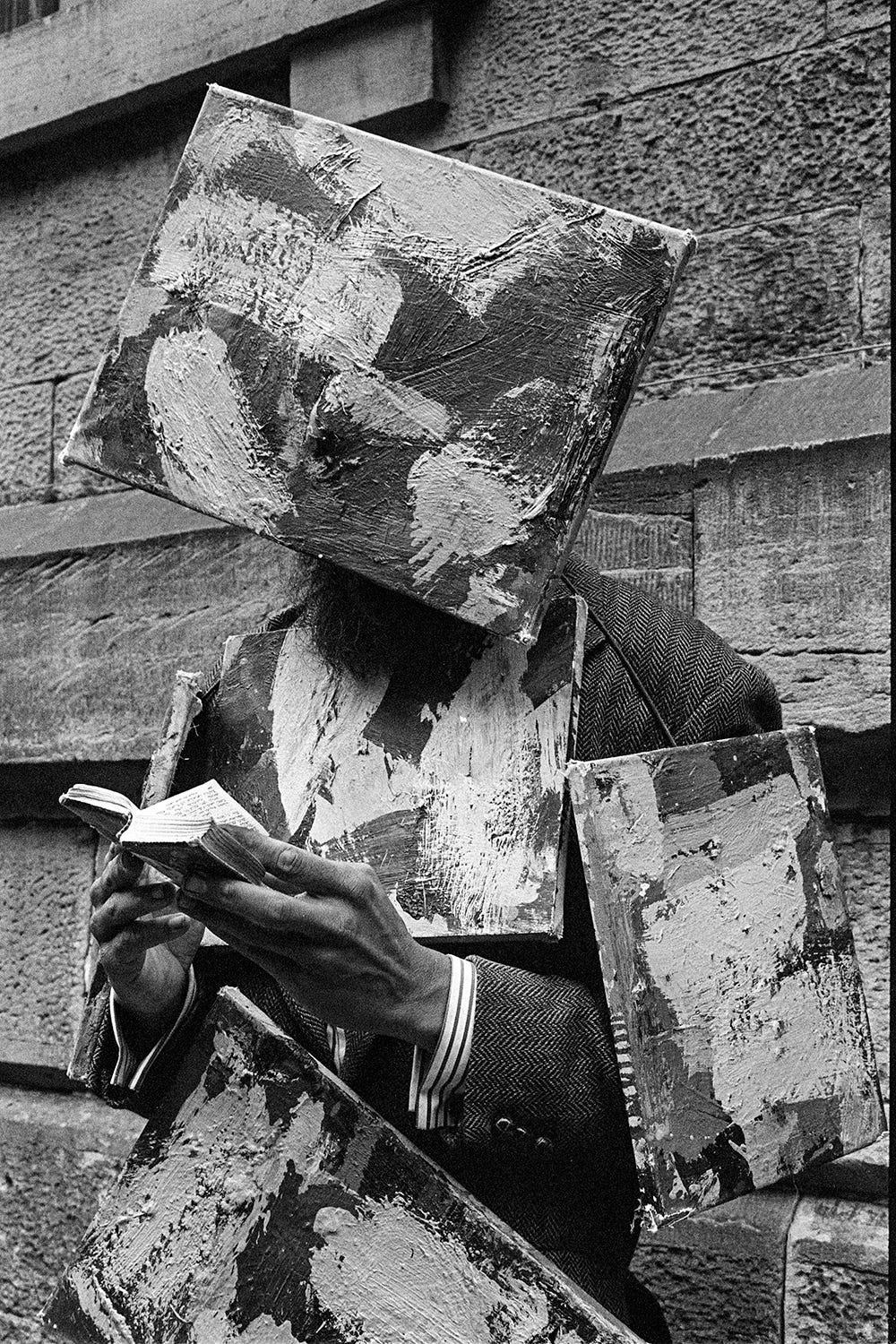

Turning to film, the most notable release in 2023 has been Josh Ethan Johnson's superlative YouTube series, Wrong Side of the Lens. Featuring a wide range of street photographers including Jill Freedman, Daniel Arnold, Valerie J. Bower, and 16 others, the series is a masterclass, in itself, of contemporary street photography.

It's been 10 years since Cheryl Dunn premiered her documentary, Everybody Street, and the film doesn't seem to be any less popular in street photography circles. Tim Huynh's 2020 documentary Fill the Frame isn't spoken of as fondly. It may not share quite the same impact as Johnson's series, but is, nevertheless, an enjoyable watch. There are several documentaries of individual photographers I return to again and again. Elliott Erwitt's Silence Sounds Good, the BBC's 1980s Master Photographers series episode on André Kertész, and All Things Are Photographable, the excellent documentary on Garry Winogrand. Though I have yet to see it, Paul Sng's film on Tish Murtha has received remarkable reviews and one can only imagine it is full of inspiration and influence for contemporary street photographers. While not street photography, the arresting documentary on the work of James Nachtwey, War Photographer, is one I return to year after year.

Courses

Udemy, Skillshare, and a smattering of other MOOC platforms have Street Photography online courses to learn at your own pace, though I can vouch for Magnum's excellent The Art of Street Photography as a thorough primer into the practice. Instructors include Richard Kalvar, Martin Parr, Bruce Gilden, and others. The videos are accompanied by a comprehensive workbook. For more intensive, in-person options, several universities and photography schools have foundational and intensive street photography courses. ICP in New York, for instance, has a well-reviewed and thorough intensive course.

Workshops and Mentorships

The world of practical street photography workshops is bustling and vibrant. A simple Google search takes one through many different workshop offerings from the reasonably priced Streetsnappers or Street Photography International, through more high-end offerings, to the frankly absurd in, for instance, Eric Kim's 5-hour workshop for $3500. I am not comfortable commenting on or recommending workshops I have not participated in, but I can say that if you pay for that, you've more money than sense, especially since the self-proclaimed Bitcoin Billionaire evidently doesn't need the money. With so many options there is bound to be a wide variance of quality. If spending some time in one of the myriad workshops available is of interest, then the advice is, of course, to 1st find one that offers the help that you need, then look for testimonials and reviews to confirm the money will be well spent.

Mentorships have become more popular in recent years, and many of the street photographers offering small-group workshops also offer 1-on-1 mentorship opportunities. Again, I am reticent to recommend anyone in particular, having not undertaken the available mentorship programs. My advice for anyone considering this option is to research the photographer who will be the mentor. Read as much of their work as possible and assess how their mentorship may help or hinder your practice. From the photographer, ask for testimonials from previous, satisfied mentees. Before signing on the dotted line, as it were, have a discussion with the mentor, ideally meet, and understand in what form the mentorship will take. Often an instructor may offer some soft mentorship after a workshop or course has finished. This is at the discretion of the instructor, however, I have heard some positive results have come from such occasional, informal arrangements.

Masterclasses

Many workshops are led by talented, engaging and charismatic street photographers, however, there is one option that sits a step above and that is the street photography masterclass. Not always named as such, for our purposes here I consider a masterclass to be instruction, review, and/or practical coaching by a photographer in the top tier of street photography. It is in the form of a masterclass that I had the opportunity to spend time at Magnum in Paris with one of my favourite photographers, Richard Kalvar, and then later last year with the imposing figure of Bruce Gilden at Leica in London. For different reasons, both experiences were pivotal in my growth as not only a street shooter but also an overall photographer. Masterclasses are available from a variety of sources, the aforementioned ICP, for one. B&H and Adorama often offer masterclasses at various photography expos and conferences. Leica Akademie is a popular venue in locations around the world. Magnum also offers a collection of street photography-based masterclasses, not only in their London, Paris, and New York locations but in cities all across the globe. Additionally, Many high-level photographers will offer masterclasses through their website or smaller organisations. Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb, for instance, offer a masterclass through La Luz Workshops, which comes highly recommended.

There is no shortage, then, of opportunity to step forward in street photography and make better work. From on-demand lessons through comprehensive, intensive courses, to masterclasses, there are myriad ways to learn and improve.

Technology

While some may argue the technology of street photography is the same as it ever was - a rangefinder, f/8 and be there - in reality the hardware and software that support our practice has seen dramatic change in recent times. Digital cameras see incremental improvement year after year with larger and more effective sensors, smartphones continue to add optics from traditional photographic powerhouses Hasselblad, and Leica; editing, processing, and filtering software add to the tools available in our digital darkroom; and of course, there is the looming spectre of AI.

Cameras

Though some photographers, Martin Parr and Richard Kalvar among others, make excellent use of D/SLRs, they are not considered conventional cameras for street photography, noisy and conspicuous as they are. Mirrorless cameras, absent the alerting slap of the mirror, are much better suited for the street. In the last 18 months, Leica has improved on the M10 and given the world the M11/11-P digital rangefinder, and their most recent compact, the Leica Q3 with its Summilux 28mm lens. Ricoh improved on the GRIII, with the GRIIIx and replaced the wider 18mm lens with a more street-friendly 28mm lens, and there are excited rumours in street circles that the GRiv may be making an appearance next year. Fujifilm's X100V is now pushing 4 years old but remains a favourite for street shooters and is certainly a more affordable option than the Leica. And speaking of the red dots, the German company has reintroduced the M6 analogue rangefinder to their product range, though the second-hand market is so vibrant with reliable film Ms, I recommend finding one pre-owned.

Smartphones

Smartphones have seen an exponential rise in use for street photography and while iPhoneography is popular, I am still not convinced of their suitability as a serious tool. While RAW files have been available on phones for some time whether native or through 3rd party apps, the size of the lens and sensor capturing the data does not match what can be recorded through a professional or prosumer digital camera. That being said, the OnePlus 12 smartphone offers a hardware-assisted 3rd Generation Hasselblad Camera for Mobile, the dual-camera system of the iPhone 15 Plus is certainly the best Apple has had to offer so far, and Google's Pixel 8 Pro has also a strong offering for street photography.

Software

Whether editing and processing RAW files from a camera or scans from film, there is plenty of software out there to make the job easier. My film workflow incorporates Silverfast 9 for scanning, Adobe Lightroom Classic for cataloguing, and Adobe Photoshop for everything else. For digital, I use Lightroom for both cataloguing and initial RAW processing before all contrast and other adjustments are done in Photoshop. I suspect this is similar to most readers. Alternatives like GIMP and Capture ONE are also popular, but the latter seems more suited to serious portraiture. Luminar Neo is the new kid on the block and while I have not had the opportunity to use it, it has gathered some critical acclaim since its launch last year. Other software is useful, of course. I enjoy Alien Skin's Exposure 7 suite of film emulations and use them often with my digital pictures. Topaz Labs have AI-powered tools that denoise, sharpen, or upscale photographs. My experiments with all 3 tools have been somewhat hit-and-miss, but this may be my deficiencies rather than those of the software.

AI

All this brings me around to the looming spectre of AI. The explosion of Artificial Intelligence across our lives in the last 18 months has been both a spectacle and a concern. For street photography, AI represents a material threat to the practice and its authenticity. The joy found in the practice comes from having the good fortune or anticipation to be there and make a picture of something striking and memorable. The hunt for the photograph is an art form in and of itself. Can this feeling be found on the end of a blinking cursor? Then, of course, there is the issue of authenticity. Some images generated through prompts of software such as Midjourney and DALL-E 3 are so photorealistic that they represent a material threat to what is real and trustworthy. With such improvements in generative AI, the very authenticity of street photography is at stake.

Public Perception and Ethical Considerations

In the 10-year gap between taking my last photo and returning to photography in the early days of the pandemic, I found that the climate of street photography had experienced a tangible shift. In my early days learning the ropes in 2006/7, I felt little apprehension making photographs of the public on the streets of Glasgow, Paris, and Warsaw. In returning to, and concentrating on, street photography in 2020, I experienced more anxiety than I previously had. I attributed this to 20 years of ageing, to having more life experience and less impetuousness, and to several years of psychoanalysis in therapy. In short, I understood it to be something internal within me. I was rusty, I needed to shake off the apprehension while retaining the awareness and empathy. Over the 3 years since, I have found, however, that there has been an unmistakable change in the public perception and photographic practice of street photography.

With the explosion and subsequent fatigue of the use of social media, and the flagrant abuses of our data by the major social media companies, it is unsurprising that privacy has become a divisive issue for many. In the absence of agency against such abuse by corporations or surveillance by our governments, street photographers have become an easy target in this skirmish in the culture wars. In reality, the practice of street photography has always been found to walk a balance along the knife-edge of capturing authentic moments of life, often without permission or consent, while also portraying our subjects with dignity, respect, and empathy. It is our responsibility as street photographers to do so.

Privacy

The issue of privacy is a thorny one and we should be sensitive, though not subservient, to it. While I hold strongly that when in public one has a limited expectation of privacy, street photographers should be aware of the power dynamics at play. Just because we can photograph someone doing something, it does not mean that we should. In my classes, and in discussion, I often assert that each individual street photographer must draw their own ethical lines. I have mine and you will have yours.

On the Place de la République in Paris last year, a group of teenagers played a game of football. Jumpers, well... bin bags, for goalposts. As I photographed, one approached me and asked me to stop. I acquiesced but with the group's permission, I continued to photograph without faces. Later, when considering why, Richard Kalvar pointed out that many of these teenagers may be illegal immigrants or refugees and thus prefer not to be photographed. Someone in our group suggested that with phone cameras, CCTV, and tourists, they were likely photographed hundreds of times that day. Someone else suggested the logical extreme that it is for them not to risk going out in public at all. Here is where we need empathy. In my impetuous youth, I may have taken umbrage to the challenge. Save for the risk of being set upon by the group, I could have chosen to continue photographing in the bloody-minded indignance that it was my right to do so. Maturity and the development of my ethical lines inform how I chose to work.

Intention and Entitlement

My own photography often comes from a place of wry or ironic humour in the traditions of Winogrand, Erwitt, or the aforementioned Kalvar. Sharing the latter's philosophy, it is never my intention to mock the subject of the photo but to make light of the curious situations we as people find ourselves in. It is, I admit, a subtle distinction but one that is nevertheless important. My photography, and the street photography that I love, is never cruel. There is no enjoyment in cruelty. I do not wish an audience that would find pleasure in such cruelty.

Earlier in the year, Anthony Morganti wrote an article questioning his love for street photography. In it, he referenced a Paulie B video in which Trevor Wisecup, in anticipation of making a photograph of someone, claimed to be about to ruin a person's day. Wisecup has a reputation as being an enthusiastic, nice guy, his photos are great, and there is certainly a Gilden-esque bravado in front of Paulie B's camera, however, I feel this schtick is indefensible and it casts other street photographers in a bad light. Gilden himself often warns other photographers from trying to do what he does. Last year, he told our class in London that if every street photographer was Bruce Gilden, there would be no street photography at all.

Much of the public's recent consternation of street photography rails against this perceived entitlement and I suspect much of it comes from what they experience of Gilden-clones and other aggressive types out on the street as well as viral TikTok and YouTube videos. The overwhelming majority of candid street photographers are not so antagonistic or confrontational in their photography. Bravado or not, we should not relish the prospect of fucking up [someone's] day. Again, I stress, that whether the photo is made or not comes down to where the photographer draws their ethical lines, however, if the choice to make the photograph is contentious then at the very least we must consider and own this.

Consent

The most surprising development in mindset from millennial street photographers to those of Gen-Z is the debate over permission and consent. Last year, I turned to Reddit in an attempt to find a community away from Meta and Twitter. What felt promising quickly became a disillusionment and I left as swiftly as I arrived. In one conversation about an unpleasant confrontation in street photography, I was surprised to see such animus directed at the photographer. He could have handled the confrontation better, it is safe to say, however, the issue was that he made the photo, at all, without permission or consent, being accused of abuse. In another conversation, inexplicably on the street photography subreddit no less, a photographer was accused of sexual assault for nothing more than photographing a woman on the street. Even accepting hyperbole this seemed somewhat beyond the pale.

An oft-repeated axiom in street photography is that it is better to ask forgiveness than to seek permission. Those who subscribe to this, myself included, posit that in seeking consent, the scene changes irrevocably and we kill the authenticity of the photograph we previsualised. Candid photography has been made in this way since the very first peopled photograph. Daguerre presumably did not scuttle down onto the Boulevard du Temple to ask the shoeblack's consent. With exceptions, Cartier-Bresson, Winogrand, Meyerowitz, Moriyama, Webb, and the pantheon of street photography masters make their photographs without seeking permission.

It can nevertheless be argued that there are many things perfectly admissible in days gone by that are unacceptable today. Though we may conclude that candid photography is justifiable, it is something that we must nevertheless consider. Here, I believe the crucial question is of the photographer's intention. Despite what social media may lead one to believe, most people don't care one way or the other if their photograph is taken. They may be confused, bewildered, or even flattered, and sometimes they may be angry, but the overwhelming number will be ambivalent. If the photographer is honest and sincere in intention, often a simple smile can remove any form of altercation. No one's day is ruined.

Conversation and debate over the ethics of street photography will continue and photographers from across the gamut of styles and philosophies will add their voices. Street photography has been said by some to have an image problem and while I do not believe the problem extends quite so far - social media has its silos and bubbles - it is notable that several well-respected voices have spoken out and voiced their unease with the conduct of some in our community. Generational divides suggest a fracturing of practice and for some a shift towards a more consent-driven form of street photography in the future and it will be interesting to see how this changes the aesthetic of the work created. However we choose to photograph, with permission or without, it is our responsibility to conduct ourselves ethically and with empathy towards those we photograph.

The Change in Urban Dynamics

Since Atget paced the streets of Paris documenting the development of Vieux Paris to the modern city we now recognise, street photographers have made pictures of great urban change. Compare the photographs of Bernice Abbott's New York to those of Jill Freedman, to those of Mathias Wasik and a different city can be seen each time. As our major cities change, so does the street photography associated with them. As neighbourhoods are developed, and gentrified, they often become affordable only to the wealthy. Many transform to dull homogeneity. Where once, for example, small, locally owned businesses operated shopfronts, now a Starbucks is found on every corner.

The Death of the High Street

At the same time, the death of the high street has caused related concerns. Last year, I spent some time photographing on Oxford Street in London, and on Sauchiehall and Argyle Streets in Glasgow. All famous, bustling centres of commerce, ripe for exciting street photography. And yet, when shop fronts weren't boarded over, or covered with hoardings promising a future reopening, they were occupied with endless American Candy stores - rumoured to be fronts for organised crime, and branches of Poundland. Exaggeration, maybe, but hyperbole paints a picture. Our high streets and neighbourhoods are changing and as they transform, so does the street photography we make within them.

With the high street logos abandoning the shop fronts and moving into malls, they take their customers with them which causes a small but inarguable inconvenience for street photographers. These malls are privately-owned spaces and as such often have their own rules about photography within their walls. Street photographers still make photographs within malls, of course, but there is more risk at hand with mall security around each curve or corner.

Privacy (Again)

As we have touched upon, the issue of privacy continues to be a contentious issue in society, not only within the community of street photographers. Joris Lechêne is a social communicator, trainer, and social media activist who often speaks of the encroachment of private ownership onto public spaces and the loss to communities as a result. It is through much of Joris’ social media content that I have come to better understand issues such as privilege and decoloniality, however, it is his videos on private vs. public spaces that put these issues into sharp relief. Many public spaces that we once took for granted, and where we could make street photography without fear of confrontation, have been deemed private whether appropriate to do so or not.

In 2011, for a film made for the London Street Photography Festival, Hannah White sent 6 photographers out onto the streets of London to make photographs on public land and to do so as they would on any given day. The endeavour was to test the private and state policing of public and private space, and particularly highlight private security firms and their reactions to photographers. Stand Your Ground is an eye-opening film. All 6 photographers were stopped at least once and 3 encounters led to the police being summoned. In 12 years, this phenomenon, and the entitlement of these private security firms has only become more bold.

For many years, a movement of First Amendment Auditors has risen up in the US, and it has found its way to Britain. Similar to Hannah White's movie, they test the bounds of the powers of policing public versus private spaces, however, one thing stands apart. While their cause is a righteous one, they often do more harm than good. Though there is no doubt the police or security overstep, almost all of the interactions or confrontations these self-appointed auditors share on social media are aggravated by their own poor behaviour or attitude. One more cynical than I would suggest they inflame the encounter for clicks. I suspect the situation for street photographers is made worse by this calculated confrontation.

The issue, however, remains. While there are legitimate heightened security considerations in light of forever wars and terrorism, private security will often overstep, simply because they can. As such, it is important to know the laws of the country and the bylaws of the city where one is photographing. In that way, one can be confident in discussions with private security, even in the face of police intervention. In Hannah White's movie, in all cases when police were summoned, they sided with the photographers as they were careful to stick to public land.

One cannot argue that there has been a marked increase in the general public's awareness of issues of privacy in the last 10 years. People feel burned by the overbearing surveillance culture, of CCTV cameras on every corner, facial recognition software, of police videoing the faces of participants of protests, and tech corporations' flagrant abuses of our data generated on their platforms. Though regrettable, it is at least understandable that individuals may take their frustrations out on the jobbing street photographer that they are unable to do so against their state or big tech. We may feel aggrieved by this misplaced opprobrium, but we should sympathise with it, and we may need to come to accept it as part of the risk taken when making our photographs.

Crowded Metropolis

As our world recovers from the trauma of the pandemic, the centres of metropolis, be they London, New York, or Paris, have again become increasingly crowded. Heavier streams of people provide cover for the candid street photographer to blend in, though it becomes more difficult to isolate a subject, with a high danger of clutter. Equally, however, this provides more opportunities to layer and organise the chaos into a dynamic, energetic rectangle. Despite the aforementioned death of the high street, these centres of commerce still bustle with activity. Each visit when I return to Glasgow, I am astonished by the apparent battalions of street performers and buskers around every corner. Gone are the days of bucket drummers and crusty bearded fellas with acoustic guitars. Peppering city centres now seem to be endless factory-produced karaoke singers aping Lewis Capaldi along to an iPhone with a Bluetooth connection. Such boring photography.

Hovering around these performers is the public that they hope may scan the QR code emblazoned in front of them. What do these punters hold in their hands? The ubiquitous smartphone, of course. I appreciate that here, I may be a curmudgeon, however, one can't walk down a city street without seeing a gallery of shop doorways populated by people checking their phones. Like street performers, the public distracted by smartphones is low-hanging fruit for street photography. Such photos are easy and with rare exceptions are almost always dull. In the opinion of one 40-something Scotsman, at least, pictures of Joe Public gazing into the black mirror are to be avoided, which is difficult given the ubiquity of the mobile device.

Representation and Othering

Despite what right-wing populists might proclaim, our cities are not full up. Whether immigrant communities have existed for generations, or they are a result of refugee crises triggered by recent wars or the climate emergency; that multiculturalism is a net gain to our society is inarguable, and it's not even close. Steering away from the politics, lest this essay become polemic, I will concentrate only on the photography.

Our collective view of life in our towns and cities benefits from a wide range of cultural perspectives, especially as those in the future look back on our photographs as historical record. How this white, middle-class, straight 40-something experiences life in the public space will be different to the point of view of, hypothetically, a 25-year-old, queer, Syrian refugee. A wide diversity of views and stories benefits street photography, and society as a whole.

When we photograph, with our specific point of view, we do so either by making photographs of subjects just like us, or people distinct from us. Such differences may be societal, cultural, generational, racial, ethnic, sexual, or economic, among others and so we are far more likely to photograph difference than homogeneity. These differences can be experienced as near to us as a metro stop or 2, or as far as a trip across the world. In meeting these differences we must at least be aware of them, any implicit bias they may inject into our work, stereotypes we may reinforce, and how we portray those in front of our lens.

Last year, Magnum ran a fascinating Professional Practices course on the topic of working with NGOs. Alongside Representatives of several organisations, Jess Crombie, a consultant who works with NGOs to explore ethical complexities in their storytelling, spoke to the class about representation and the concept of othering. Jess co-authored The People in the Pictures for Save the Children, and was instrumental in writing ethical guidelines for the collection and use of content. While these sessions, lectures, and conversations were not focused on street photography, they have strengthened and informed my understanding of representation since.

When we photograph those of other ethnicities, economic conditions, or gender identities, whether in our neighbourhoods, or in far-off foreign countries, there is a stronger expectation today to avoid exoticising them and to avoid seeing the subject as the other. It is argued that to do so is to look upon them with inherent inequality and thus project our biases and stereotypes onto them, whether intentional or not.

This is not to say we cannot make street photography of those different to ourselves, nor to second-guess an opportunity for a photograph in the moment, but it is to encourage readers to think more of cultural sensitivities, customs and etiquette. We should be aware of the choices we make and think critically about our work and the effect it may have on those in front of our lens.

The Art World

As with all manner of entertainment such as cinema, concerts, and sporting events, the art world suffered during the lockdowns of the global pandemic and has been slowly returning to whatever can now be considered normal since.

Galleries

Galleries across the world continue to give space and time to street photography. It would be folly to begin to list even a small number here. I would begin at MoMA and ICP in New York, and by the time we reach Stills in Edinburgh or Street Level PhotoWorks in Glasgow, I would have lost what I imagine is an already dwindling readership of this article. Closer to home though, Warsaw lost its Leica gallery, 6x7. Situated a floor above the Leica store, this was a home to some excellent street photography exhibitions, the last of which I saw there was a Meyerowitz retrospective. A sad loss.

Exhibitions

There were several notable street photography exhibitions this year. There was, for instance, a major retrospective of Daidō Moriyama at the Photographers' Gallery in London. The Folkwang Museum in Essen has been showing Rafał Milach's Archive of Public Protests exhibition, and the sadly-missed Elliott Erwitt has had a retrospective exhibition travelling Europe this year.

Festivals

Gothenburg's Street Photography Festival was held in September and by all accounts was a cracking success. Matt Stuart held a session, as did several photographers from the Nordic region. The month-long Mexico Street Photography Festival took place across most of November, with exhibitions, talks, photo walks, and review sessions across the month. Thomas Hoepker, Newsha Tavakolian, Matt Stuart, and Maciej Dakowicz exhibited work among many others in Tehran's Street Photography Festival exhibition which closed just this month. Matt Stuart was doing the rounds this year and made an earlier appearance in April at the Italian Street Photography Festival but alas Paolo Pellegrin had to cancel due to work commitments. ISPF, nevertheless, had a great program of photo walks, sessions and talks.

There were some regrettable losses. London Street Photography Festival took a hiatus in 2022 with the intention they would see us in 2023, however, they didn't return. We may see their likes again, but judging from their social media there is no indication of an imminent return. While continuing throughout this year with a slate of workshops, Miami Street Photography Festival also had a hiatus in 2023, and one hopes it will return in the coming year.

Trade Shows and Conferences

Having attended neither Paris Photo or Photo London this year, I can't speak from experience but from reports, there was no particular focus on street photography and from one anecdote, several galleries were sniffy about the very idea of carrying street photography. Nevertheless, in Paris there were sessions devoted to both Saul Leiter and William Klein, and in London, Martin Parr spent some time discussing his favourite topic of conversation, the photo book.

Competitions

As is the convention, most festivals have their annual competitions and those above were joined by some prestigious street photography awards through this year. Fuji, Leica, and Sony all have their competitions, and websites such as LensCulture and Street Photographers Foundation have their contests too. The winners of such awards are at the subjective mercy of the juries selected for this year. In every contest I have reviewed this year, I would have chosen one of the finalists over the winning photograph - every time, emphasising that inherent subjectivity.

In Memorium

Leaving behind an indelible mark on the world of street photography with his often joyful visual storytelling, Magnum photographer Elliott Erwitt died this month at the age of 95. Born between the wars in 1928, Erwitt's prolific career spanned over 7 decades and the master continued photographing and working until very recently. His life, including his recent trip to Cuba, was documented in Adriana López Sanfeliu's documentary, Silence Sounds Good. Quoted as saying that all the technique in the world doesn't compensate for the inability to notice, Erwitt was famous for his unparalleled eye for wit and irony within a scene. A master of timing and emotion, his timeless and iconic black-and-white photography inspired and influenced many across generations, myself included. Thank you, Elliott. Thank you for being serious about not being serious.

Thank you for reading the inaugural State of Street Photography essay. I am sure that across so many different subjects, I have neglected to mention or cover some angles. With your help, this time next year, I hope to discover and highlight so much more of the world of street photography.

So, what did I miss? Are there other topics I should discuss next year? Let me know in the comments.

And Finally…

Stay tuned for Issue 14 of Photos, mostly coming on the 27th of December.

I’d be very grateful if you would share Photos, mostly. Sharing with 1 or 2 friends who enjoy street photography really will help more than you may think.

If you’re a Substack writer and enjoy this publication, I’d be more than humbled if you would consider recommending Photos, mostly to your subscribers.

Thank you, and have a happy new year when it comes!

regarding one topic of the essay, i can say one thing about public perception: nobody complains, nobody does anything if i take a photo with my phone, the moment i take out my camera ... everything changes! it baffles me

Interesting state of the nation address and efficiently summarised. Looking forward to the paid content to come!