Not long ago, I looked wearily into our bathroom mirror at my shorn temple to see that indeed, hidden by the now departed longer hair, had been a small, though prominent, fresh patch of grey making its debut. There had been signs, of course. I caught myself describing music on the radio as a noise. The banished weight around my midriff, absent for years, had begun to reappear. And I am not enjoying the current battle with my ageing knees. Nevertheless, it was the grey hair that bore the weight of every one of my 44 years. I would like to believe several years of therapy have given me a belated self-awareness and I do check myself when I can. The music may be noise but then it's not made for me. As I think often about the looming spectre of AI in the visual arts, I do wonder if I may be a doddery Abe Simpson, angrily shouting at clouds.

AI is experiencing its gold rush moment. This year already, experts have warned that AI could have existential consequences, generative art gave us the worst Marvel TV title sequence, and Paul McCartney says AI is gifting us one final Beatles song. With considerations as broad as creativity, copyright, reality, and representation, how will AI affect the practice and authenticity of street photography?

AI and Visual Art

Anyone with a passing familiarity with the internet, from those who dabble to the incurably online, will recognise the shower of grifters that travel from one tech innovation to another. Of course, there are countless online denizens using their knowledge and skills for good, but notice that it is the same faces who moved from Crypto through Web3.0, NFTs, and the Metaverse who are now proclaiming AI is the next big thing, all with the same another-White-boy-with-a-podcast energy.

Last month, a user of Adobe's Firefly posed the question "Ever wonder what the rest of the Mona Lisa looks like?" before posting an image that used Adobe's new Generative Fill to show a wider view. To say the critical response was withering is to be polite. The audacity, though, to look at a 520-year-old painting and think, how can I improve that? Ever wonder what the rest of Robert Frank's Hotel Lobby Miami Beach 1955 (The Americans 25) looks like? No, because the frame is the picture, the intent of the artist, not a restriction enforced upon the photographer. Frank has cropped the negative to include precisely what he, the author, wants to show.

This year, German artist Boris Eldagsen made headlines with the cleverly titled image, Pseudomnesia. A beautiful vintage picture of two women together in an intimate moment. It was, however, a false memory. A fake. The image had been generated using AI and entered into the Sony World Photography Awards competition to provoke debate. It won.

AI is in its infancy. It is crawling, blinking, out of the sea. When it reaches its metaphorical enlightenment, its industrial revolution, or its own space age, there is no telling how sophisticated it may become. While algorithms are already being used to edit, process, and adjust photographs, removing tedious repetitive tasks, there are numerous examples online of newspapers, magazines, blogs, websites, and other organisations introducing AI to their businesses for more significant work. Whether this leads to a mass reduction of the workforce remains to be seen.

In this conversation, it is often said that newspapers of record would not knowingly run faked or generated images as photojournalism, however, how long until the difference is imperceptible? In May, a fake image of an explosion at the Pentagon that appeared online caused a brief dip in the stock market. Stepping back though, are AI-generated images any different in concept from courtroom sketches? Might we see, instead of a photograph of some world event, an AI interpretation of it? Photorealistic renderings of Trump in the dock?

Training the Data

Even a cursory Google search will illustrate quite how polarising the debate on AI-powered generative art is. On the one hand, there are the copyright abolitionists and tech absolutists who care not for the rights of the countless artists whose work was used to train the models on which the AI generates its output. On the other, are those that believe generative art is vampirical, animated by those who have come before, while simultaneously an existential threat to those living, giving life to a pale imitation of the real thing.

Generators like DALL-E and Midjourney are trained on countless millions of copyrighted images, all created by someone. These images are scraped and processed without ever asking for the creator's consent - and there certainly is no suggestion of compensation. In their open letter, Artistic Enquiry called it effectively the greatest art heist in history. What is clear, though, is there is only so much training data. As the volume of AI-generated images increases, and they are caught up in the nets scraping the internet for data, then AI will begin to feed itself. Output will trend towards the homogenous and there will be a distinct lack of diversity.

Diversity. That's another hot potato in this seemingly endless debate. As the popularity of generative art grew, artist and researcher Minne Atairu began training a data set to generate portraits based on Instagram downloads of Black models. Despite Atairu's best efforts to overcome them, the system produced repeating stereotypes indicating issues with coded, underlying biases.

While one might argue that as artists we are also trained and influenced by those who have gone before, a key and crucial distinction is that we have our past experiences and interpretations to guide us. When sent lyrics to a ChatGPT-generated song in the style of Nick Cave, the antipodean songwriter responded to the eager creator in characteristic fashion.

This song is bullshit, a grotesque mockery of what it is to be human...What makes a great song great is not its close resemblance to a recognizable work. Writing a good song is not mimicry, or replication, or pastiche, it is the opposite. It is an act of self-murder that destroys all one has strived to produce in the past.

Yikes.

Street Photography and the Looming Spectre of AI

In my late-night, pre-sleep, doom-scrolling I was luckless enough to find myself watching a hashtag-hustle-type explaining to his podcast bros how he prompts AI-generated images. I was tired. His delivery was insufferable. Though my pedantry peaked when he exclaimed that as money is no object, he could use the best camera available, then chose the Leica M10. It’s 2023 mate; the real issue though was his insistence that he could make any picture he desired in the style of.

It took no time at all for these artless grifters to find their way to indulge in some of the aforementioned grotesque mockeries that are completely unreflective of any technique, skill, or experience they may have and instead mimic the aesthetic style of the masters by cribbing from stolen imagery. While some of it is technically impressive and is worryingly photorealistic, it lacks any semblance of soul or character. The subjects do not have lives, stories, thoughts, or feelings. In truth, these images are exactly what one would expect from a robot mimicking a street photography master, failing to scratch the surface to reach a deeper appreciation or understanding of why the shutter was tripped. Midjourney images in the style of Cartier-Bresson do not share the same sense of geometric flair or surrealist timing. Others in the style of Garry Winogrand lack any of his odd and compelling nature.

For street photography purists, the spirit of the practice is loaded with the endeavour of existing in the moment, experiencing the scene, and being in the right place at the right time, with the camera ready to capture something striking and memorable. The hunt for the photograph is an art form in and of itself. Street photography is not easy. It is often the photographer having the good fortune or skilful anticipation to be there to make the photo that is so celebrated. Walking 10 to 15km in a day, feeling that maybe it was a bust, only to turn around and witness something funny, ridiculous, or beautiful, and click. There is no feeling like that found at the end of a blinking cursor. Substituting the skill, experience, intuition, and anticipation with a text prompt undermines the whole practice.

The real concern, though, is not the soulless emptiness of AI-generated street images, but the inevitable doubt of authenticity they will bring to all street photography. Though most pictures from AI generators still have a distinctive plastic sheen to them, the technology is improving version by version. The most recent update to Midjourney has made an appreciable step forward. These images are becoming so realistic as to be a threat to what can be considered real and trustworthy. A recent scandal concerns one Michael Christopher Brown, a photojournalist who decided it would not be in any way ethically questionable to generate AI images of Cuban refugees and sell them as NFT artwork. When discovered, he was dragged over the coals, and rightly so, however, the images were convincing enough for many.

That a street photographer may spend years walking the cities of the world to make their best, most unique photographs only for them to be looked upon suspiciously on publication with the implied or explicit suggestion that the moment didn't happen or that the photographer wasn't there is a real concern. In the future, negatives, contact sheets, and raw files will become crucial to street and documentary photography to ensure and prove veracity. With the improvements in generative AI, the very authenticity of street photography is at stake.

AI in street photography, what do you think? Am I being a Luddite, or is there cause for concern? Let me know in the comments.

Digest, June 2023

It is often said that one good street photograph per month is a decent return. I wrote about setting realistic expectations and using the failures and nearly-theres to learn from and improve.

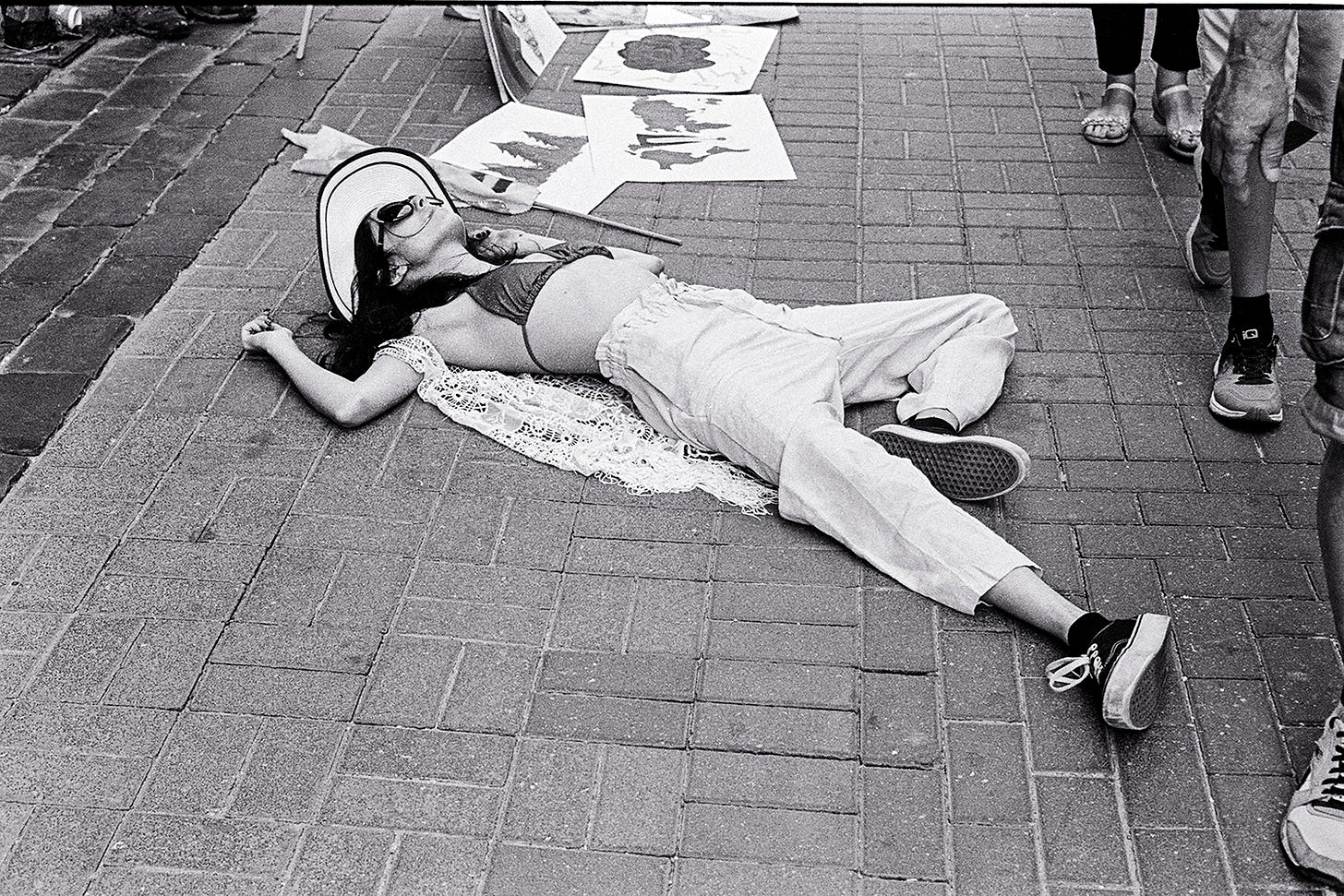

In the space of just 4 days in early June, I shot 11 rolls of film at 2 separate Warsaw events. I collected some of the photographs together in a couple of short photo essays.

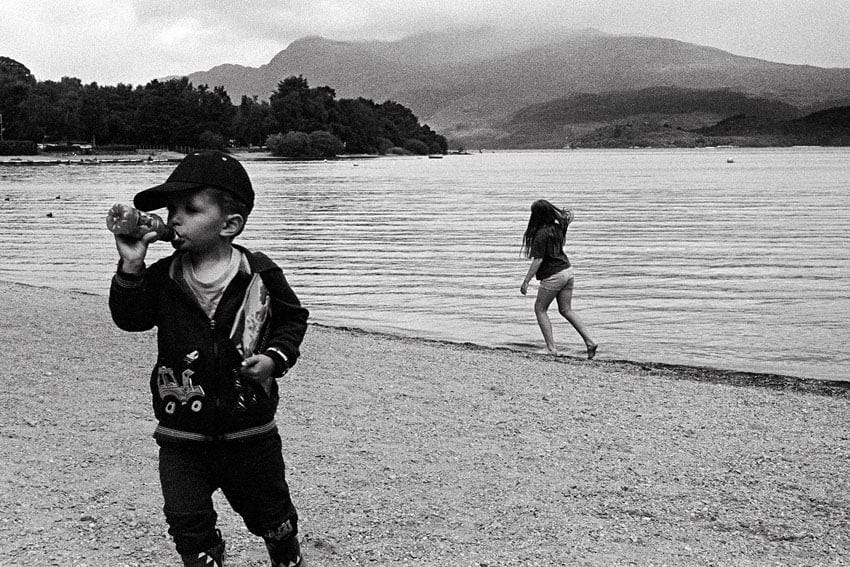

My latest article on Shoot It With Film is a travel story with a collection of photographs from my post-lockdown trips home to Scotland.

At last, I have found time to begin my oft-threatened-though-never-started series of top 5s on my blog starting with some 1960s guitar pop.

Returning to my semi-regular series, I’ve continued watching the 100 greatest British movies of the 20th century as chosen by the British Film Institute.

94: The Belles of St. Trinians | 93: Caravaggio | 92: In Which We Serve

Some Photos

And Finally…

Stay tuned for the next recommendations email coming on the 12th of July. If you’ve enjoyed issue number 8, I’d be very grateful if you could subscribe, share, and recommend it to any street photography-loving friends.

This newsletter is free to read, however, I've recently left corporate life and returned to school, so if you like what I do, please consider buying me a roll of film. You can do so by clicking here, or by aiming your camera at the QR code below.

I'm partial to some of that Tri-X 400 if you're asking. Thank you!