Issue 13: The Fugitive and the Infinite

Or: Street Photography and the Bohemian Curiosity of the Flâneur

It would be fair to say that Charles Baudelaire had complex feelings on the matter of photography. Despite finding himself in front of Nadar's lens on several occasions, the great French poet and critic of modern art, writing on the cusp of romanticism and modernism, proclaimed that the photographic industry was the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies. In his essay On Photography, published in 1859, he was critical of its mechanical nature and contemptuous of its ubiquity, decrying a madness, an extraordinary fanaticism [that] took possession of all these new sun-worshippers. His biggest criticism, however, was for the medium's precision. Such mechanical reproduction could not possibly be considered art.

A year later, in his acclaimed essay, The Painter of Modern Life, Baudelaire wrote further on the aesthetics of modernity and adopted an obscure journalist and illustrator reporting for the Illustrated London News as the personification of modern, visual art. Cast as the unnamed bohemian hero Monsieur G., for he humbly refused to be named, Constantin Guys had spent many years travelling the world as a reporter, and as a correspondent during the Crimean War. Baudelaire describes Monsieur G. in glowing, admiring terms and sets him as a flâneur, a wanderer, whose mainspring of his genius is curiosity. He is a passionate observer of the world, someone trained to study the world around him and distil it down to the wine of life.

The crowd is his domain, as the air is that of the birds, and the water the fishes. His passion, and profession, is to espouse the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate observer, it is an immense joy to take up one’s dwelling among the multitude, amidst undulation, movement, the fugitive, the infinite.

- Charles Baudelaire. The Painter of Modern Life (1863).

It is this enigmatic portrayal of the flâneur that has been romanticised and passed down from 19th-century French life to today: The curious, aesthetically attuned and attentive spectator wandering amongst, though detached from, modern life. The connoisseur of the street.

Documents Pour Artistes

As one century marched with alacrity toward another, a middle-aged gentleman was walking the streets of Paris making photographs of the great city's boulevards and arcades. His calling card read E. Atget, Creator and Purveyor of a ‘Collection of Photographic Views of Old Paris.’ Earlier in life, Eugène Atget had spent time in the merchant navy before trying his hand at acting but eventually found his way to the camera. He began making documents, visual reference, of the city for artists. His love for the often hidden charm and beauty of the arrondissements and the life that populated them grew, and photographing the streets of the French capital became his raison d'être. As Vieux Paris was reshaped by systematic modernisation, Atget was consumed with the project of memorialising the pre-revolutionary neighbourhoods that were disappearing.

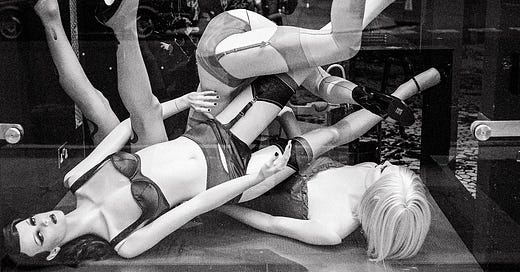

With his hat atop his head and engulfed in a black cloak, Atget would walk the streets of the city, his view camera carried by its tripod, slung over his shoulder. When something caught his attention, he would stop, set himself, and make a photograph. So varied was his work that archivists have split it into several categories and numerous subcategories: Picturesque Paris, Art in old Paris, Environs, Costumes, Interiors, and Paris Parks name but a few. In his tireless flânerie, Eugène Atget discovered the vibrant life that flowed through the arteries of Vieux Paris. His, often surreal, photographs would present the viewer with shop windows through which mannequins may peer, purveyors of small trades selling their wares, and prostitutes marking time in doorways. In short, it may be argued that Atget the flâneur was the forerunner of surrealist photography and the prototypical street photographer.

The Modern Flâneur

The street photographer then, in any of its modern guises, has its roots in the not-so-bygone social character of the 19th-century flâneur. Whether it was Henri Cartier-Bresson walking the roads of Europe and Asia, Helen Levitt or Garry Winogrand on the streets of New York, Daido Moriyama in Tokyo, or Peter Turnley among others in modern-day Paris, the street photographer is the modern explorer of the cityscape, attentive eyes wide open, rapt in curiosity.

In Melancholy Objects, the 3rd essay in Susan Sontag's collection On Photography, she asserts that the photographer is an armed version of the solitary walker. Armed with a rangefinder, a medium format, or an SLR, the street photographer wanders in public spaces, a landscape of voluptuous extremes, observing with searching eyes, attuned to the rhythms and undulations of life on the street. Sontag goes on: Adept of the joys of watching, connoisseur of empathy, the flâneur finds the world ‘picturesque’. That, to me, could be the very dictionary definition of a street photographer.

To step expectantly into the rushing river of life on the street, an aimless, though hopeful, stroll across city squares, down busy streets, and through hidden walkways, is the optimistic mark of the street photographer. To be alone and yet simultaneously be surrounded by others. Whether in the photographer's home city or one far away, like the flâneur, the street photographer is happy to walk and watch with patience and interest. Not only to watch but to see. As Baudelaire suggested, [t]o be absent from home and yet feel oneself everywhere at home; to view the world, to be at the heart of the world, and yet hidden from the world, [...] one who understands the world and the mysterious and legitimate reasons for its many behaviours.

The Flâneurial Gaze

Even before I picked up a camera, for most of my adult life, when I would visit a new city, I would put my earphones in, some music on, and walk around. Not a conscious effort to get lost, but a lack of concern for keeping my bearings. In Doha, in 2012 during a hiatus from photography, I left the hotel and didn't return for 5 hours, so fascinated was I of life on this new continent. People-watching is a pastime many partake in whether they name it or not. There is a simple pleasure in just watching. Looking. Anticipating what may develop. Telling oneself the story of the people that pass by. In his writing, Walter Benjamin considered whether the flâneur, a figure keenly aware of the bustle of modern life, can enjoy the aimlessness of their existence or, in our modern capitalist world, must there be a product. Is the street photographer an unconscious answer to this need for productivity? The romantic thinks not. The artist hopes that the desire to tack on an aim to the aimlessness is nothing but an innate impulse toward creativity.

Benjamin's flâneur walks out their door as if [they've] just arrived from a foreign country, and as they do so Baudelaire's watches the river of life in its flow, so majestic, so brilliant. Atget's successors do so with a camera in their hands, delighting, as Baudelaire puts it, in universal life. To notice then, as a street photographer, is to gaze at the world through the eyes of a flâneur. Constantin Guys was an illustrator and thus free from the rules, regulations and constraints of the Académie française. Strictly held laws of art didn't apply to the way in which he could depict the world. The modern flâneurs of, for instance, Garry Winogrand and Robert Frank, however unconsciously, threw aside the expectations and conventions of photographic academia to show the world that they saw in the manner in which they saw it, drunken horizons and all. Winogrand, of course, photographed the world to see what it look[ed] like photographed.

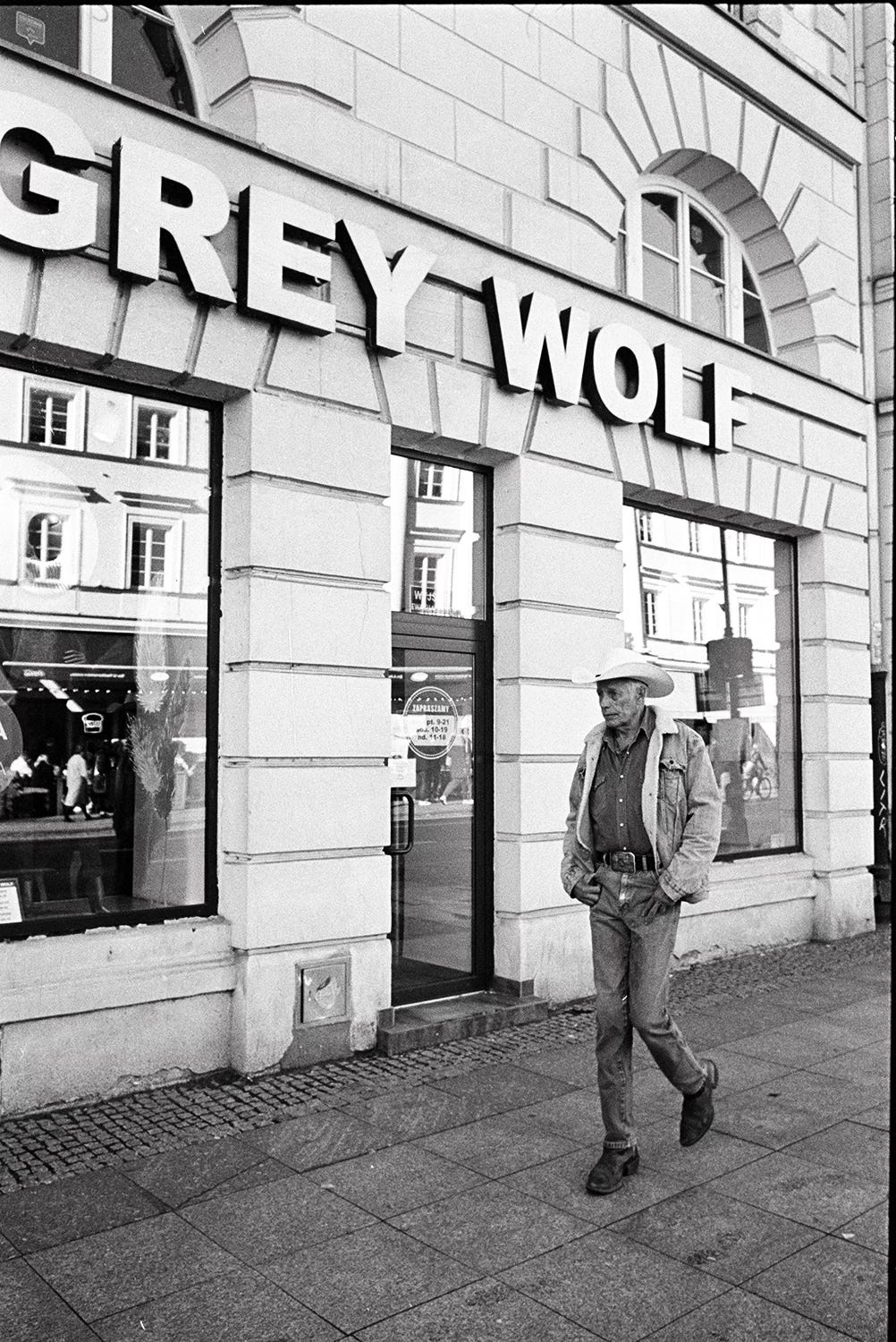

To be a flâneur is to be a street photographer is to be a flâneur. To walk among the crowd but to be separate from it. To be curious and open to chance and what may be discovered. To wander aimlessly but with aim, and see the city as a stage for all the human drama, comedy, and tragedy that may occur on its boards. To pay attention and notice small gestures, emotions, and expressions that hint towards an authentic, if fleeting, moment. Quick to react. 1/500th of a second then it's gone. In short, to be a flâneur, to be a street photographer, is to hold on to that fascination and empathy for life outside our door.

So what do you think? Are you a flâneur or a flâneuse? Do you enjoy walking a town or city with manifest curiosity? Let me know in the comments.

Digest, November 2023

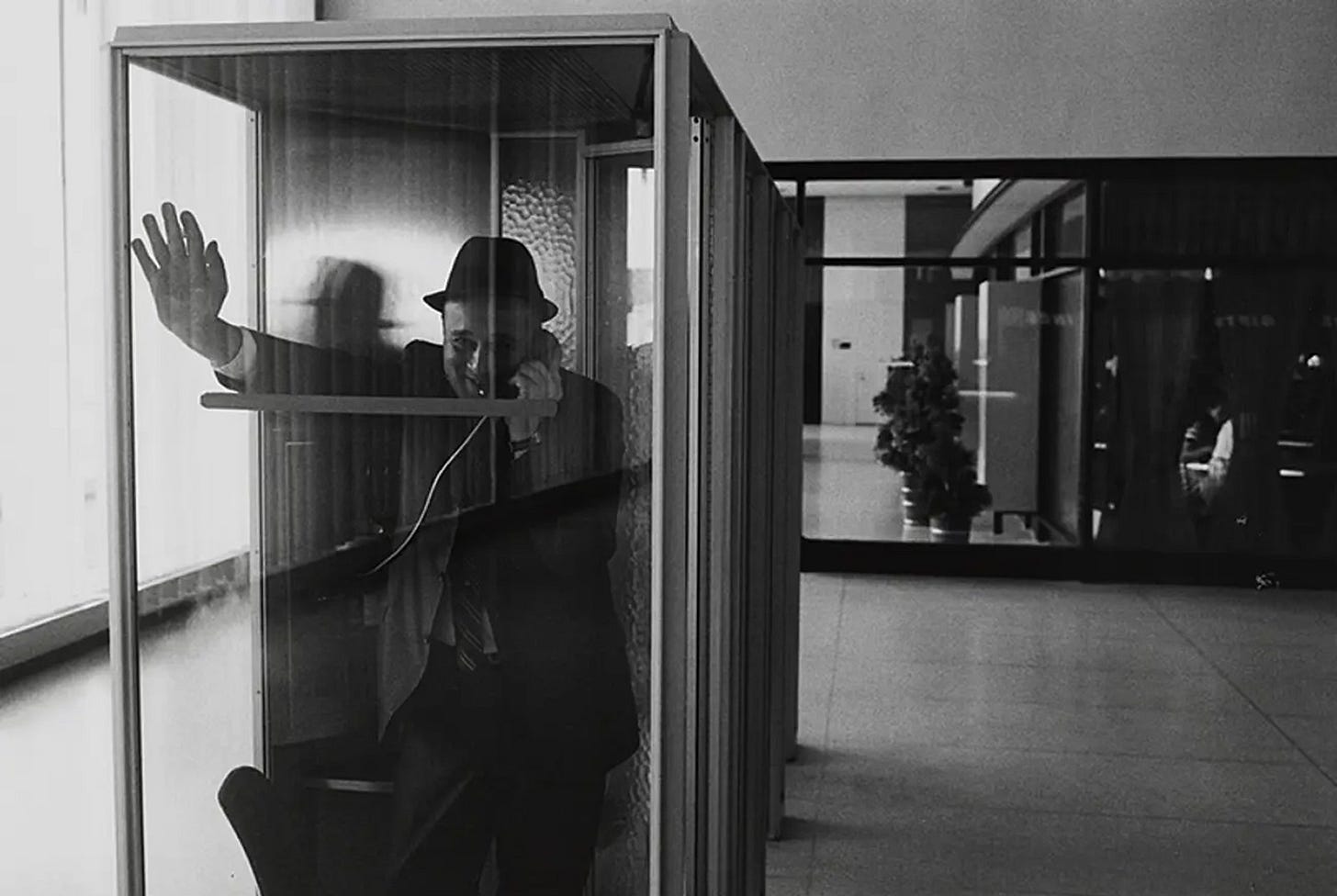

An integral tool found in the great toolbox of street photographers is anticipation. Learning to notice not only what is around but what may transpire is how many great photographs are made.

With the absence of an article for Shoot It With Film this month (stay tuned for January’s mammoth review of the Leica M3), I wrote about the importance of practice and exercise in street photography.

For almost 2 months I have followed the Polish-Palestinian protests against the genocide and ethnic cleansing occurring in Gaza. These are some of my photos. With some dismay, I expect this will be part 1 of several.

While turning it over in my head, a quote by the great modernist author DH Lawrence sparked the basis for my latest Top 5 article.

I return to my semi-regular series, continuing to watch the 100 greatest British movies of the 20th century as chosen by the British Film Institute.

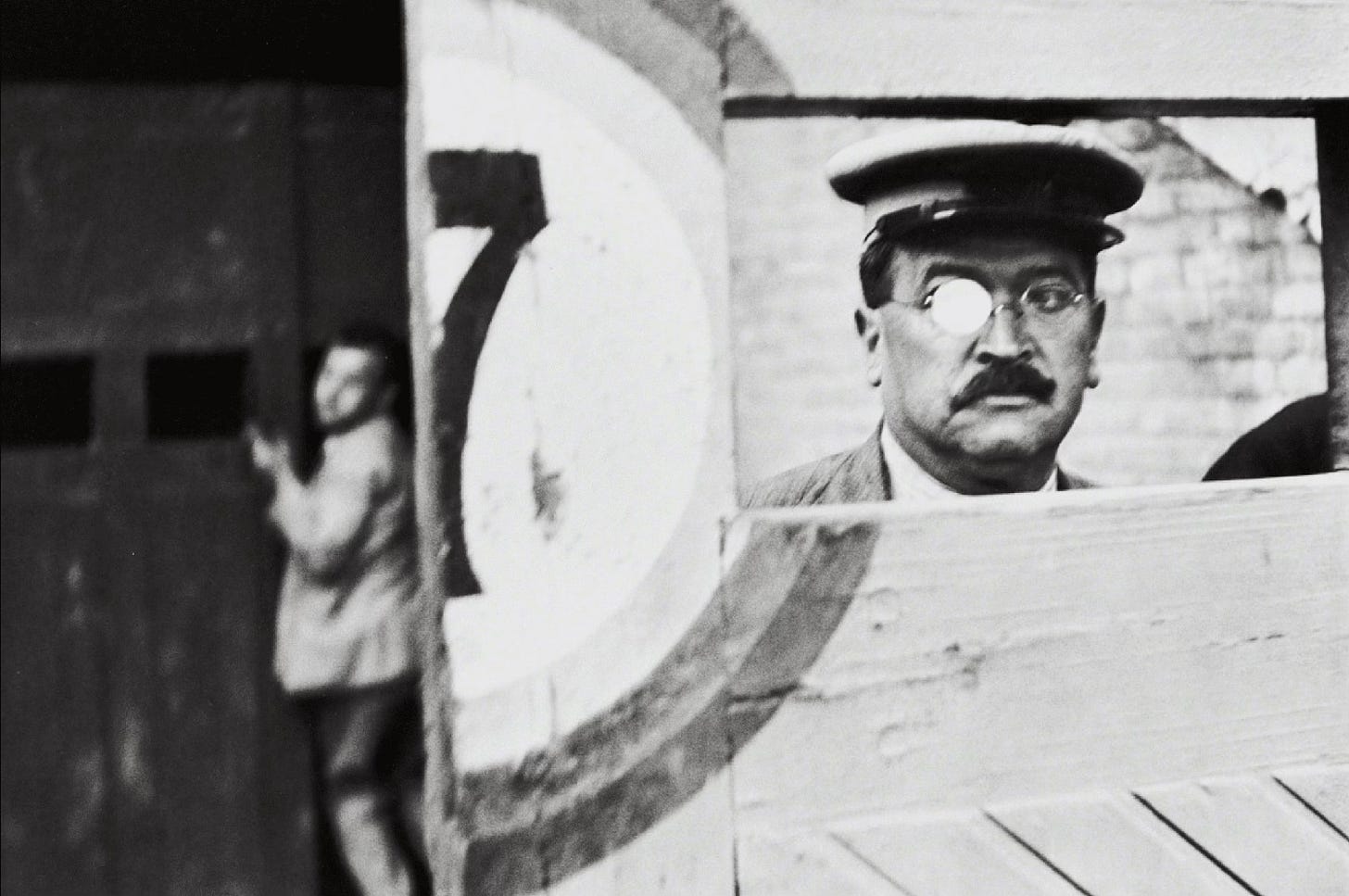

Some Photos

And Finally…

Stay tuned for the next Dispatches email coming on the 13th of December.

After last month’s postponement, the inaugural, annual Street Photography State of the Union will be published on the 20th of December. After taking advice from several writers, it will be my first content that will require a paid subscription. There will be much more in the new year.

I’d be very grateful if you would subscribe to or share Photos, mostly. Sharing with 1 or 2 friends who enjoy street photography really will help more than you may think.

If you’re a Substack writer and enjoy this publication, I’d be more than humbled if you would consider recommending Photos, mostly to your subscribers.

This newsletter is free to read, however, this year I left corporate life and returned to school, so if you like what I do, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or buying me a roll of film. You can do so by clicking here, or by aiming your smartphone camera at the QR code below.

I'm partial to some of that Tri-X 400 if you're asking. Thank you!

Fascinating and succinct - always a thought-provoking read and a visual treat.

Very nice article. Thanks for sharing!