Issue 14: You Press The Button, We Do The Rest

Or: The Kodak Revolution, Jacques Henri Lartigue, and How the Vernacular Gave Rise to Street Photography

It is almost unthinkable now that there was a time when photography was available only to those with expertise. Knowledge of physics, chemistry, and art history was required to even begin making, developing, and printing photographs. One also had to have the means so for some time this expensive, dangerous pursuit of photography was the walled playground of the wealthy. The original Wet Plate process that required photographers to coat, expose, and process the plate in one sitting often confined the expert photographer to a studio. The later invention of the more practical Dry Plate process allowed photographers to coat the plate, let it dry and expose it at a different time or place.

In the 1880s, George Eastman, a bank teller from Rochester, NY, began a flirtation with photography as he hoped to document an approaching vacation. In his experimentations with Richard Maddox's Dry Plate process, he found he could substitute the glass plate with paper. Rather more flexible than glass, paper could be spooled behind the shutter, and thus was born the roll of film. Eastman later founded the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company and began selling his patented rolls of dry-coated photographic film to photographers. Whether or not he enjoyed his holiday has been lost to history.

The Democratization of Photography

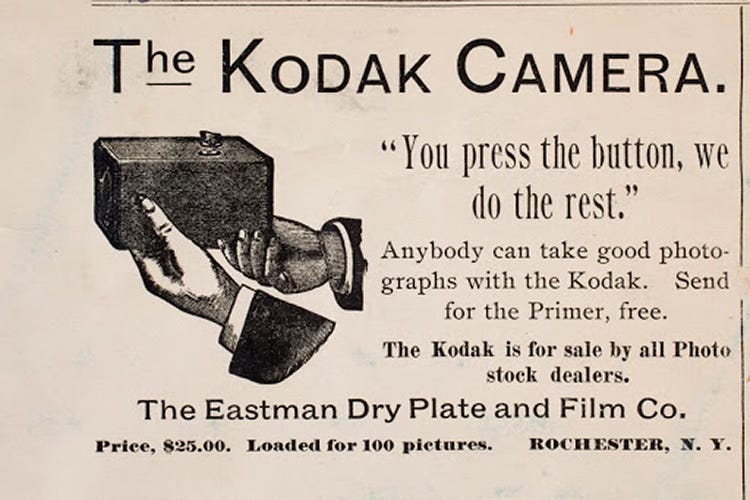

A born entrepreneur, George Eastman's vision was to make photography accessible to the masses. In 1888, he produced a simple box camera, The Kodak. Named for a word devised when playing word games one evening with his mother, Eastman believed the unique name with the strong K would be memorable. He was not wrong.

With some flair for advertising, Eastman sold The Kodak with the memorable slogan, You press the button, we do the rest. The camera came pre-loaded with a roll of paper film 100 exposures long. It had fixed focus and no viewfinder and was by definition, if not by name, a point-and-shoot. No expertise was required for use and there was no messy chemistry to concern oneself with. When spent, the camera, with exposed film still inside, would be shipped back to Rochester for processing and printing. The prints would be returned with the camera, and a new roll of film installed, ready for 100 further button presses.

With such simplicity, the Kodak was a great success. For the first time, photography was available to millions of casual enthusiasts. The process was customer-friendly, easy, and uncomplicated, and it sparked a revolution.

The Kodak Revolution

Free from the constraints of the studio and any need for scientific understanding, the Kodak excited a national craze for snapshot photography. Believed to have been coined by Sir John Herschel in the mid-19th century, the term was stolen, as much of the predatory language of photography had been, from hunting. A snapshot, whether through barrel or lens, is a quick shot made without careful aim. With the absence of a viewfinder, the Kodak was very much a snapshot camera. Unencumbered by the need, or capacity, for careful composition the snapshooter discovered by way of experiments and happy accidents a new photographic vocabulary. As cameras were carried in one's daily life, gone were the still, staid, sober portraits of the salon, and here to stay arrived the kinetic enjoyment of life in the world and a procession of subjects encouraged to smile.

Clubs were founded and magazines published, all to allow these Kodak Fiends to share in their love for this new fad of photography. Just a decade after the Kodak was introduced, there were over 1 and a half million roll-film cameras in production and millions of photographs, with their imperfect framing and spontaneous composition, were made every year. Middle-class consumers all across America and the Western world were indulging in this new-found hobby. Such was the ubiquity of the snapshot, Queen Victoria was snapped by her daughter-in-law, the photo-mad Princess Alexandra, and the Kodak, in the hands of protagonist Jonathan Harker, even made a cameo appearance in Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula.

The vast impact that this mass adoption of photography had on the world was plain to see. Within only a few years, photography had gone from a highly specialised practice to near-ubiquity. Grandparents and children alike made photographs of their families and lives. Such was the youthful enthusiasm for photography, that Kodak's next camera, launched in 1900, was advertised for children. The Brownie was sold at a reduced price, costing only $1. Processing cost only 40c and to have the camera returned, and reloaded with film, only a further 15c. Now, photography had escaped the domain of the middle class and was available to all but the poorest of families.

Jacques Henri Lartigue and the Snapshot Aesthetic

Born to a wealthy family, Jacques Henri Lartigue had the opportunity to begin making photographs as a young boy of just 7. Though now considered a master of 20th-century photography, then he was an enthusiastic, gifted amateur making photographs of his life as a playful, fun-loving boy. As a demonstration of the keen culture of amateurism that fostered his photography, Lartigue soaked up many different styles. Biographer, Kevin Moore, said of Lartigue that he understood how to capture the essence of a moment, playing and experimenting with his snapshots.

Lartigue's photographs overflow with energy and movement. Set beside the pictorialist masterpieces of the time, the difference is stark. The contemporary pastoral photographs of the pictorialists seem frozen in time, whereas Lartigue's snapshots seize the motion of leaping relatives, racing motor cars, and mischievous pets and spill with joyful, playful exuberance.

When Lartigue's boyhood photographs were discovered by the photographic world almost 50 years later, he was found to be a prototypical predecessor of many of the street photographers now considered masters today. His photography typified the cultural shift from the posed photographs of fine art photography of the time to the candid, kinetic moments that he captured.

The Vernacular

Though the Photo-Secession and The Linked Ring pushed photography towards the art world with great success, the explosion of amateur photography uncoupled what John Szarkowski later referred to as functional photography from fine art and offered photographers a different path. Vernacular photography, the term used to contrast many other manners of the use of photographs from that of fine art, may include journalistic, commercial, scientific, medical, forensic, clerical, administrative, or even, as Susan Sontag describes them in her essay, In Plato's Cave, snapshots as souvenirs of daily life.

As the small, handheld amateur cameras were developed into professional models - for instance, the Leica introduced by the Leitz Wetzlar company in 1924 - amateur photography led the way to a professional use of the vernacular. Photographers began to document wars, photojournalists recorded newsworthy events, and police photographers captured evidence of crime scenes. Portraits were made for official documents, mugshots were taken to identify criminals, and x-rays were exposed to identify broken bones. As Sontag continued in In Plato's Cave, to collect photographs is to collect the world, and among all of this, prototypical street photographers such as Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and André Kertész did just that.

Artists were contemptuous of the vernacular though its influence began to seep through. The painter Edgar Degas adopted the fragmentation of the photographic frame. In his 1874 painting, La Classe de Danse, he shows signs that his art was finding influence in photography. How the teacher leans on his cane, the contortion of the girl scratching her back, and the way elements are cut off by the frame are all things one may not have expected in an oil painting before the advent of photography. Later, Cartier-Bresson would find influence in the open form of Degas' paintings that would further inform his photographic compositions.

Vernacular photographers, whether amateur or professional, cultivated a strong aesthetic that has persisted and cemented itself in practice through the years. Though much vernacular was considered vulgar by fine art photographers, it had a regenerative effect on the practice. Like the novel replacing the epic poem, the vernacular succeeded pictorialism in what the Russian literary critic Viktor Shklovsky termed rebarbarization; a perceived vulgarity replacing a played-out art form. This alternative to art evolved and grew into the social documentary, photojournalism, and street photography that exists to this day.

The Rise of Street Photography

The visual language of street photography has evolved over many years and can trace its lineage not from the staged formality of the photographic studio or the fine art traditions of the pictorialists, but from the spontaneous and candid nature of the vernacular, particularly the snapshot craze. Like the snapshot, street photography often eschews the strict conventions of composition and incorporates the informal aspects of the vernacular. Strong street photography captured within the walls of a 35mm frame, whether mundane or brimming with interest, or whether anticipated or instinctual, makes a picture that echoes the energy and immediacy of the snapshot.

While photographing for Roy Stryker's Farm Security Administration, Walker Evans began to reassess the vernacular of snapshots and picture postcard photographs, noticing that mundane objects, scenes, and moments were often centred. He developed what he called the American vernacular and travelled the country making photographs that highlight the symbols and icons that defined the culture. Collected together, a number of these photographs became his acclaimed 1938 exhibition and book, American Photographs, a collection that was to have a profound effect on several street photographers who were to come after and cite Evans as a major influence.

One photographer who befriended Evans in the 1950s was the Swiss-born New Yorker, Robert Frank. In 1955, with the recommendation of Evans, Frank received a Guggenheim grant to travel across America and make photographs, a project that would spawn his seminal book, The Americans. Frank's photography in the 1950s took significant influence from Evans and from the vernacular tradition from which he emerged. His photographs channelled the raw, candid authenticity of snapshot photography to lay bare the stark contradictions of American society at a time of great change. So unflinching and erratic were his photographs, with their meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness, that he received much criticism at the time, though of course now his photography is considered highly influential, especially to fellow New Yorker, Garry Winogrand.

The photography of Garry Winogrand borrows heavily from the candid aesthetic of the vernacular. Citing both Evans and Frank as instrumental in the development of his own style, his photography follows in the lineage of the snapshot. To watch Winogrand work, one could be forgiven for thinking he made his photographs without taking the time to compose through the viewfinder, however, he composed as the viewfinder travelled towards his eye and often tripped the shutter on arrival. His photography is characterised by his relentless pursuit to capture the energy the nervous energy of the street, an energy he shared. In his best pictures, Winogrand elevated the everyday moments found in the vernacular to breathtaking, profound visual statements and while he would claim a picture can't tell a story, the evidence of his work would seek to contradict him.

Legacy

Pictorialist Henry Peach Robinson once posed that the carefree snapshots of the Kodak revolution made photography almost a frivolous pursuit, and [caused] it to be included with amusements and recreations. To the pictorialists, snapshots were uncontrolled and unskilled. Art, this was not. In his elective classes at the University of Texas, however, street photographer Garry Winogrand would often assert that all things are photographable. One needs only to find the right answer to the question raised by the subject to make it a picture.

The snapshot aesthetic of the vernacular, with its lax adherence to composition, convention, and the po-faced solemnity of 19th-century artistic photography, opened the door to experimentation, play. Photographers working today, from Meyerowitz to Moriyama, owe the evolution of street photography, with its emphasis on the candid and the unposed, to the explosion of the vernacular brought about by the Kodak Revolution. There is an evident path tread from the circular snapshots of the early Kodak fiends through to the iconic 35mm works of the street photography masters. Its democratisation achieved by the marketing vision of George Eastman allowed photography to bifurcate into fine art and the vernacular. In street photography, the vernacular is elevated to an art form itself, that continues to captivate and inspire to this day.

Selected sources used for this essay include:

The BBC series The Genius of Photography (2007) and its accompanying book by Gerry Badger, Photography: A Cultural History (2002) by Mary Warner Marien, and On Photography (1977) by Susan Sontag.

Digest, December 2023

Much of December has been spent making photographs for Watch Docs, Warsaw’s premiere Human Rights film festival, and then writing my mammoth essay analysing street photography in 2023, before flying home to Scotland for Christmas. I hope that you will understand and forgive me if December 2023’s digest revisits articles from elsewhere, early in the life of Photos, mostly. Articles that most subscribers may not have yet discovered. Normal digest service will be resumed in January.

My 1st collection of street photography essays on my blog answered the what, why, where, who, and when of Street Photography.

In March, for Shoot It With Film, I wrote a guide to making photographs using zone focusing.

Elliott Erwitt, acclaimed photographer and hero to many, including myself, passed away last month at the age of 95. Last year, I wrote a review of Adriana López Sanfeliu’s documentary on Erwitt’s life, Silence Sounds Good.

As the bombs continued to fall on Gaza, I attended a talk hosted by the Scottish BPoC Writers Network and Sumud Edinburgh. I wrote about some of the performance art discussed.

And finally, for December’s digest, a dip back into my blog’s archive for a look at my checkered history of writing Christmas songs.

Some (Wintery) Photos

And Finally…

Have a happy new year, when it comes! Stay tuned for the next Dispatches email coming on the 10th of January.

I’d be very grateful if you would subscribe to or share Photos, mostly. Sharing with 1 or 2 friends who enjoy street photography really will help more than you may think.

If you’re a Substack writer and enjoy this publication, I’d be more than humbled if you would consider recommending Photos, mostly to your subscribers.

Photos, mostly and Dispatches are free to read, however, as of January, there will be additional monthly paid content. This year, I left corporate life and returned to school, so if you like what I do you can help me avoid a return to the daily grind. Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or buying me a roll of film. You can do so by clicking here, or by aiming your smartphone camera at the QR code below.

I'm partial to some of that Tri-X 400 if you're asking. Thank you!

Another wonderful edition to finish the 2023 year! Thanks Neil!

This was fun to read. Thanks Neil